Counting the cost of gentrification?

Dr. Jon Reades

6 July

London: Aspects of Change

#RuthGlass60

Why so little quantitative work in the UK?

Perhaps context points away from extensive methods?

- Stronger state/regeneration focus.

- Richer conceptualisation of types of gentrification.

- More significant data limitations (e.g. Census, though see Atkinson, 2000).

Why the change now?

Rapid developments in both methods and data:

- Online real estate listings covering sales and rentals.

- Other new forms of data including social media and planning applications.

- Novel linked data which gives us access to household change and mobility.

- Improvements in computation and techniques to support wide and long data sets.

Why it’s still not easy

An play in three parts:

- Act 1: Defining (Re)Development

- Act 2: Defining Displacement

- Act 3: Measuring Change

All of these generate a lot of drama.

Act 1: Defining (Re)Development

Few domains throw up as many challenges as housing and demographic change:

- Large changes are visible, and often complex (see, e.g, Hubbard et al., 2024).

- Small changes are invisible, and often not tracked (see, e.g, Chng, Reades and Hubbard, 2024).

- Very few ‘certainties’ in the data.

- Underlying structural dimension is inaccessible.

Act 2: Defining Displacement

Understanding whether populations have ‘changed’ in very hard in a retrospective context:

- Census is a snapshot with no ‘memory’ (see, e.g., Hamnett, 2003; Watt, 2008; Slater, 2010)

- GDPR (rightly, but frustratingly) limits access to individual identifiers

- No data on situation or motivation.

Act 3: Measuring Change

Measure what matters, and what we measure matters:

- Sales and rental prices

- Skill, education, and income levels

- Household composition and churn

- Other?

So what is

the quant contribution?

‘You can’t move in Hackney without bumping into an anthropologist’ (Neal et al., 2016)

‘… qualitative strategies for identifying gentrified neighbourhoods may overlook areas that expereienced similar changes…’ (Barton, 2016, p. 92)

Test/Control

Comparison of units to number of detected relocations (Reades et al., 2023)

Distance

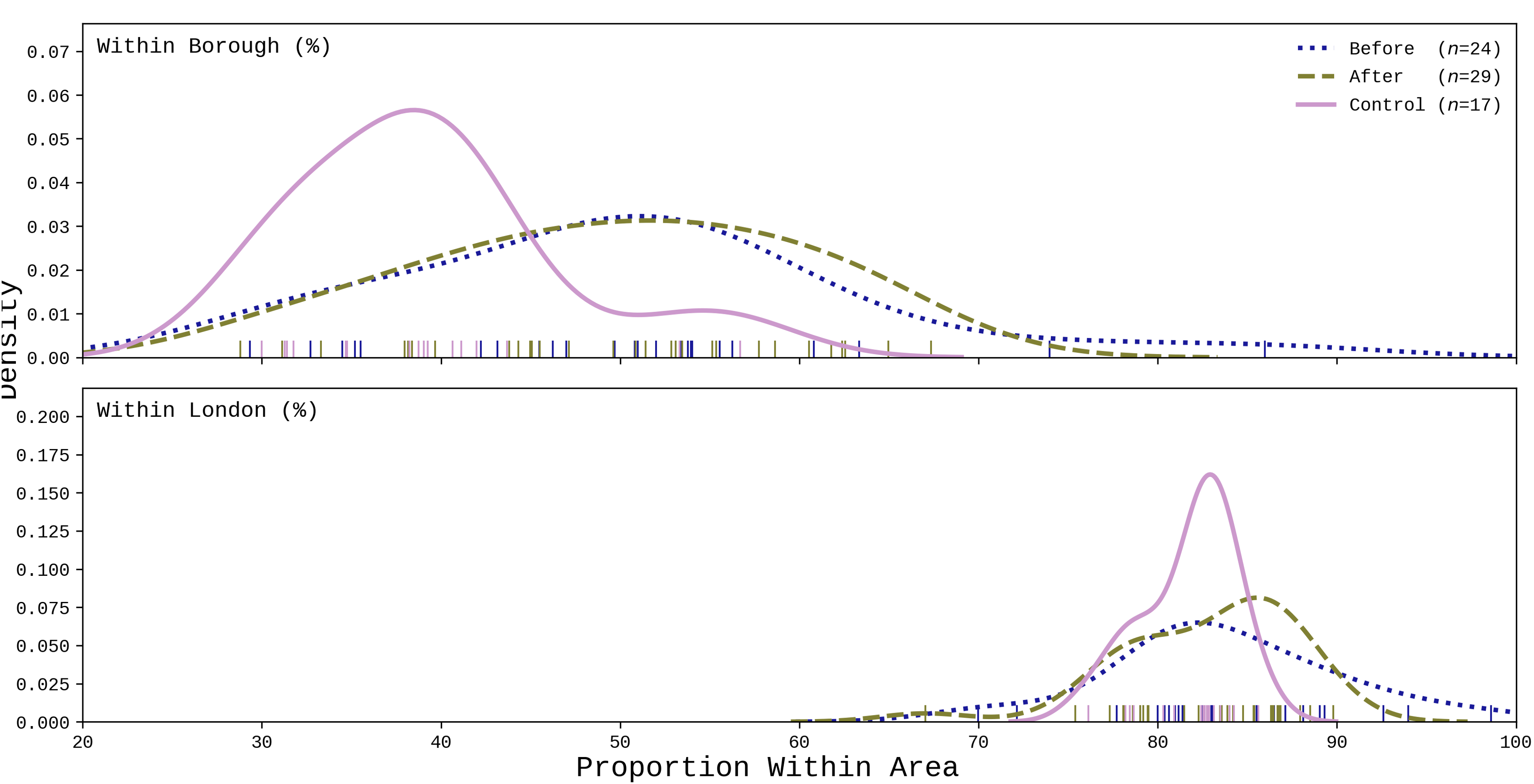

Proportion of relocations within administrative area (Reades et al., 2023)

Time

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spitalfields and Banglatown | In-movers | 0.228 | 0.353 | 0.182 | 0.135 | 0.103 |

| Out-movers | 0.251 | 0.389 | 0.164 | 0.112 | 0.084 | |

| Whitechapel | In-movers | 0.230 | 0.338 | 0.185 | 0.014 | 0.106 |

| Out-movers | 0.255 | 0.360 | 0.172 | 0.124 | 0.089 | |

| Hoxton East and Shoreditch | In-movers | 0.209 | 0.324 | 0.200 | 0.146 | 0.120 |

| Out-movers | 0.232 | 0.355 | 0.186 | 0.130 | 0.096 |

Note: Quintile 1 is the most deprived quintile, quintile 5 is the least deprived quintile.

:::

Context and Confidence

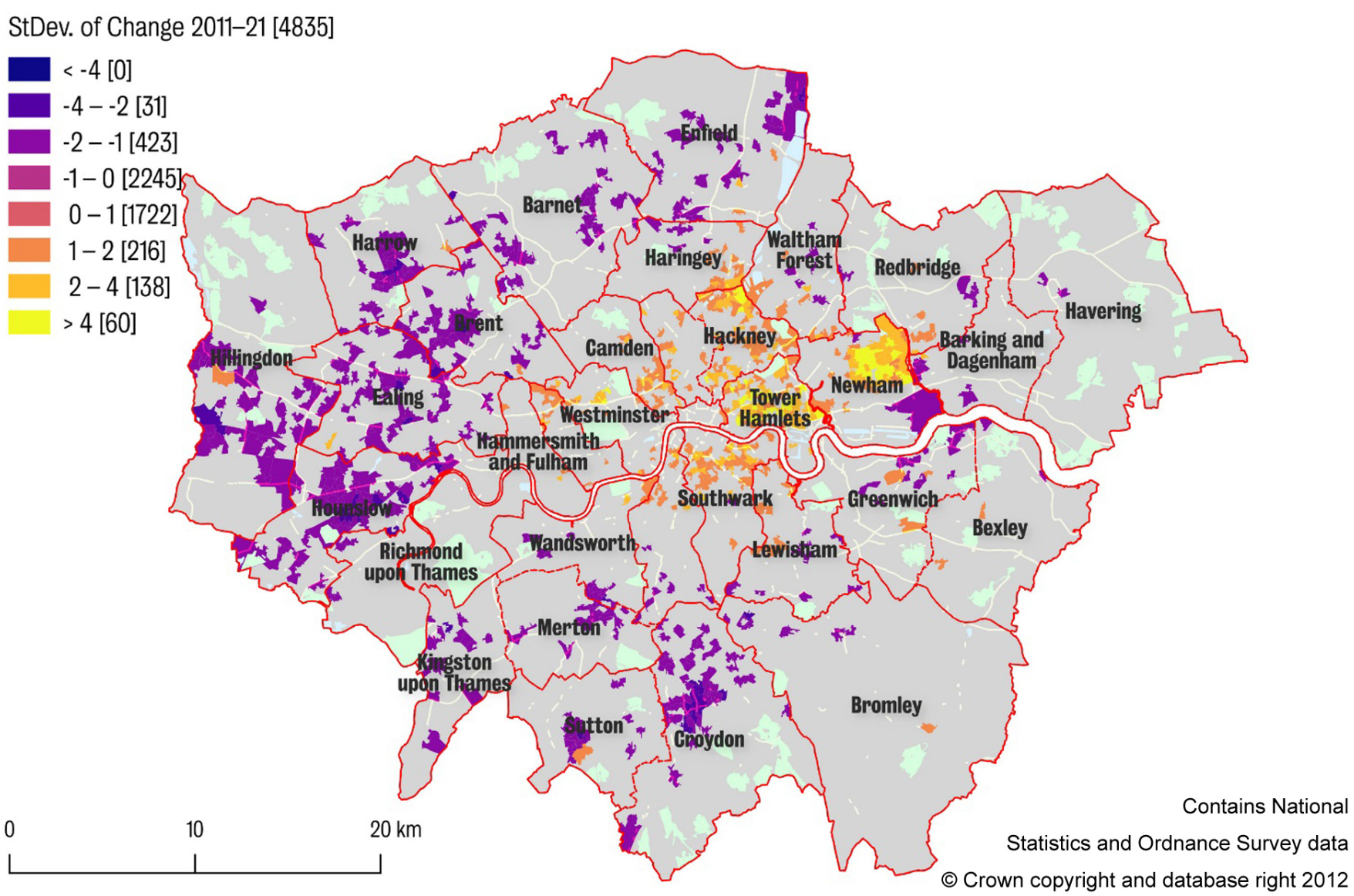

Standard deviation of change in rank 2001–2011 (Reades, De Souza and Hubbard, 2019)

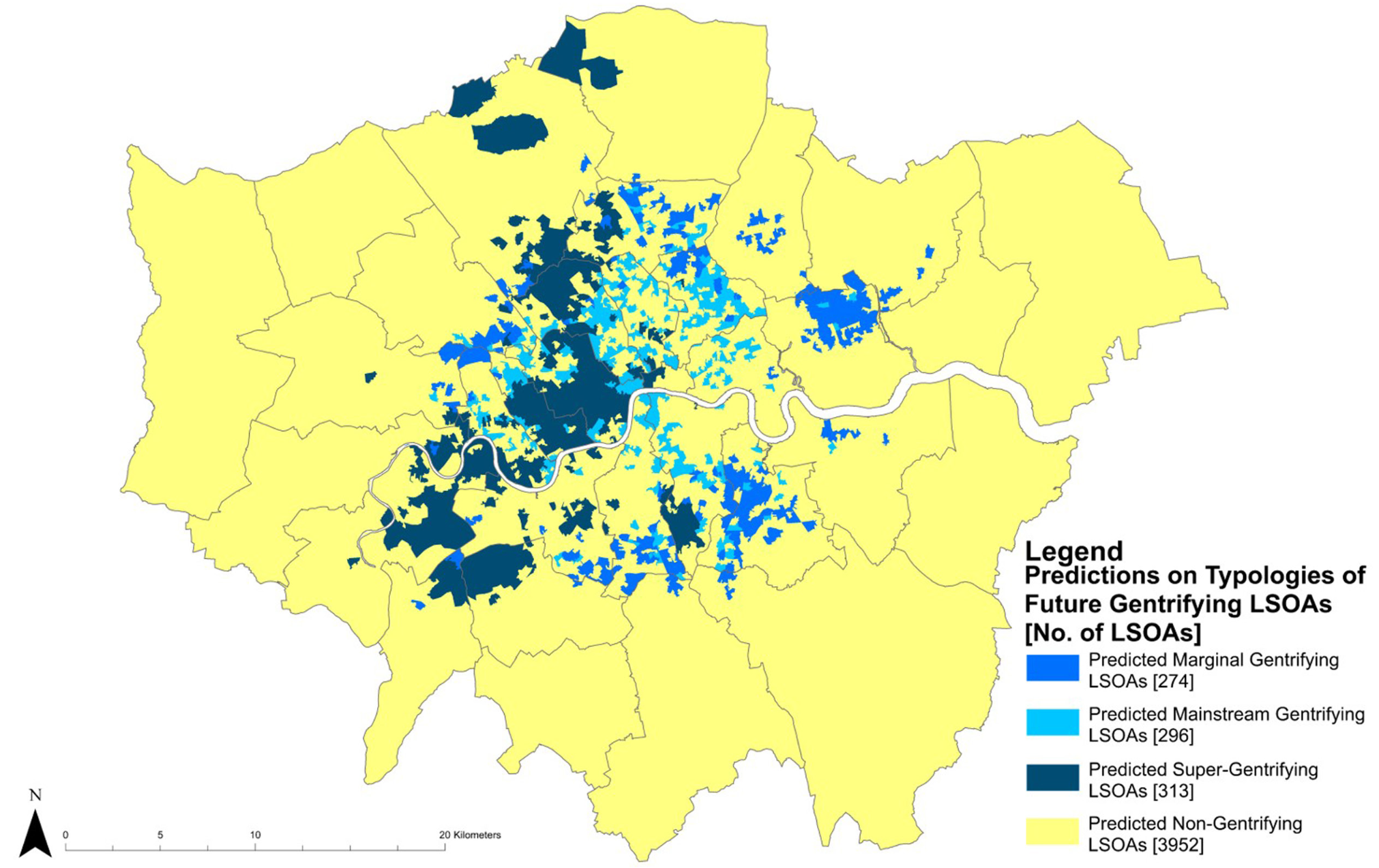

<Prediction

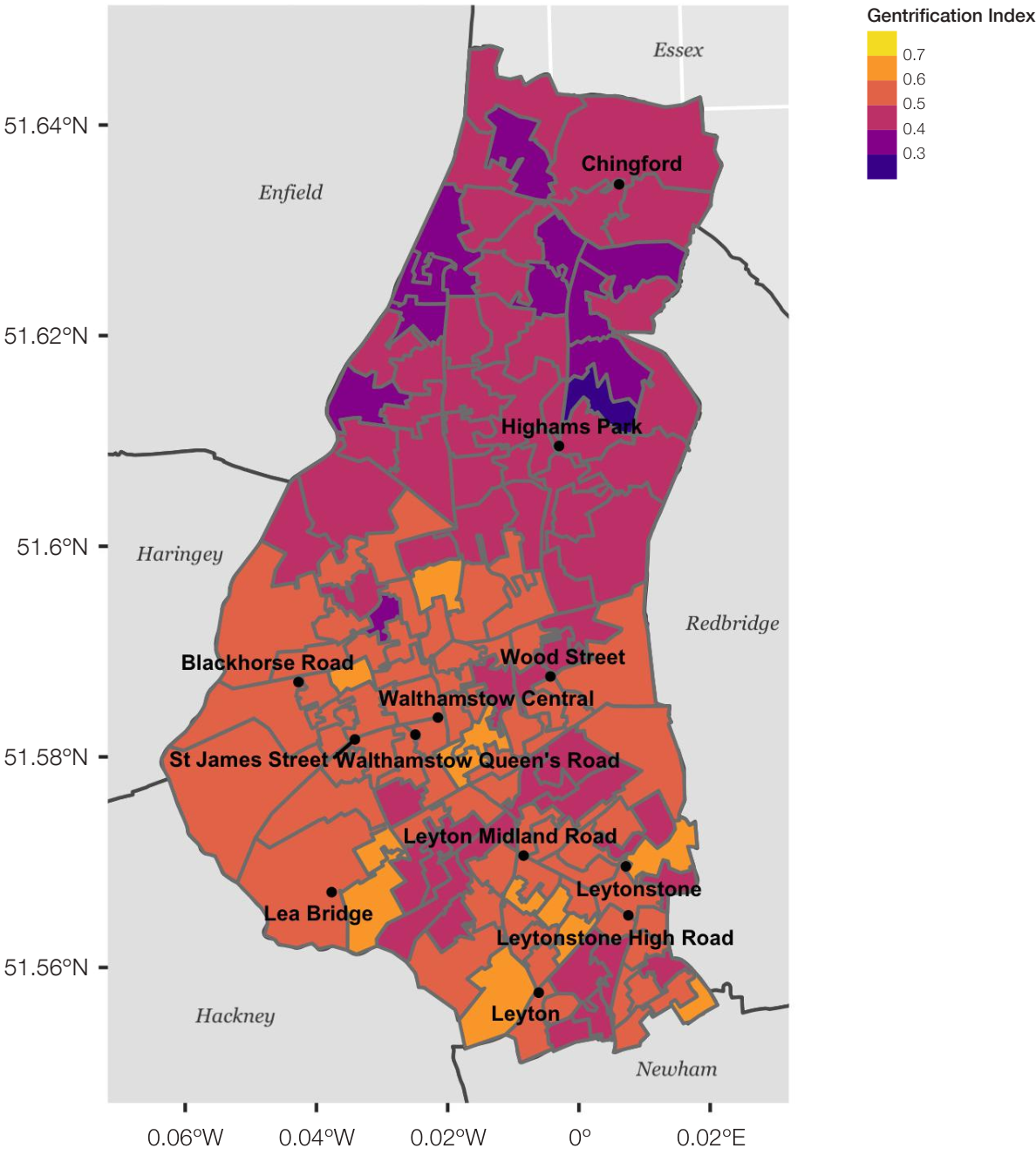

Predicted typologies of future gentrifying LSOAs (Yee and Dennett, 2022)

Wrap-Up

So what can quantitative research contribute?

And what can quantitative research learn?

One more thing…

Gentrification Bingo time!

- Paper of record for global elite

- Scene from a brewery

- On land now owned by Blackrock

- Which has successfully applied to redevelop

- Photo by the new precariat

- Who is resident (?) in local area

- … and …

- Academic just out of frame

Questions?

A partial bibliography

Jon Reades (CASA @ UCL)