first_variable = 87.0

second_variable = 9

print(first_variable % 80 < second_variable)

# proof

print(first_variable % 80)

print(second_variable)True

7.0

9In this lesson we’ll learn how to compare stuff (like numerical quantities but also words and strings) via Comparison Operators.

We’ll also see how to express logical concepts like: ” if this condition is True, then do something…“. These concepts will enable your code account for different possibilities and let it run to accordingly. They will also serve to perform assertions and to test if certain conditions have been met or not.

The most basic form of comparison is to test if something is True of False. To do so we’ll have to quickly introduce another data type, the boolean.

Booleans are different from the numerical (floats and integers) or textual (strings) data types that we have seen so far because they have only two possible values: True or False.

Did you see the str() around the myBoolean variable on the second print line? That’s so that we can print out its value as part of a string. If you just tried print("This statement is: " + myBoolean) you’d get a TypeError because you can’t concatentate (join together with a +) a string and a boolean. For more on errors see the lesson on exceptions.

How do we use booleans? Well, what if I ask you “Is it true or false that an elephant is bigger than a mouse?” So we use booleans why making some kind of comparison between two things: is it bigger? is it smaller? is the same?

Note: just so that you know, sometimes people will use 1 and 0 in place of True and False because that’s what’s actually happening behind the scenes. It’s the same thing logically , but Python views True and False differently from 1 and 0 because the latter are numbers, while the former are truth values (thus, the boolean data type).

You will need these set of operators:

| Operator | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

> |

Greater Than | A>B returns True if value of A is larger than value of B |

< |

Less Than | A<B returns True if value of A is smaller than value of B |

>= |

Greater Equal Than | A>=B returns True if value of A is larger than or equal to value of B |

<= |

Less Equal Than | A<=B returns True if value of A is smaller than or equal to value of B |

== |

Equal To | A==B returns True if value of A is exactly equal to value of B |

Here’s an initial example (without a print statement):

And further examples (with print statements):

Numerical comparisons are fairly straightforward, and you’ll see that Python automatically does fairly sensible things:

25 and 25.0 are evaluated properly25 into 25.0 automaticallyBut here are some slightly more complicated examples involving string comparisons:

print("\nA 'simple' string comparison:")

print("A" > "B")

print("B" > "A")

print("\nSomething slightly trickier:")

print("A" > "a")

print("A" >= "a")

print("A" < "a")

print("\nAnd trickier again:")

print("ab" < "abc")

print("\nhmmmm...")

print("James" < "Jane")

A 'simple' string comparison:

False

True

Something slightly trickier:

False

False

True

And trickier again:

True

hmmmm...

TrueWhy does Python think ‘A’ is less than ‘a’, and ‘Aardvark’ is less than ‘Ant’?

When comparing str objects, Python uses character unicodes. Unicode is a specification that aims to list every character used by human languages and give each character its own unique ‘number’. In Python, these codes are of type int.

To see this in action, we can use the ord function to get Python to show us the unicode for a single character:

Hopefully this output helps you to see why print("A" > "a") returns False

When there are multiple characters in a string object, Python compares each character in order. Suppose, as we do above, we have str1 as “James” and str2 as “Jane”. The first two characters from str1 and str2 (J and J) are compared. Because they are equal, the second two characters are compared. Because they are also equal, the third two characters (m and n) are compared. And because m has smaller unicode value than n, str1 is less than str2.

Hopefully this helps you to see why print("James" < "Jane") returns True

In the next two challenges, we’ve deliberately left out or broken some code that you need to fix!

Fix this code so that it returns True

Fix this code so that it returns False

So we’ve seen the comparison operators that you probably still remember from high-school maths. But sometimes we don’t want to test for difference, we want to test if two things are the same. In your maths class you probably just wrote \[x = y\] and moved on to the next problem, but remember: one equals sign is already being used to assign values to variables! As in:

To test if something is exactly equal we use the equality comparison operator, which is two equals signs together (\(==\)). This equality comparison returns True if the contents of two variables/results of two calculations are equal. That’s a bit of a mouthful, but all we’re saying is that we compare the left-hand side (LHS) of the equality operator (\(==\)) with the right-hand side (RHS) to see if they evaluate to the same answer.

A lot of new programmers make the mistake of writing = in their code when they wanted ==, and it can be hard to track this one down. So always ask yourself: am I comparing two things, or assigning one to the other?

Run the following code and check you understand why the output produced is as it is.

Before you run the code in each cell, try to think through what you expect each one to print out!

What if you want to check if two things are different rather than equal? Well then you’ll need to use the Not Equal (\(!=\)) operator, which returns True when there’s no equality between the conditons you are comparing.

Check you understand the output when running the following code

# Reset the variables to their 'defaults'

british_capital = "London"

french_capital = "Paris"

# This time python is going to print True,

# since we are comparing different things

# using the Not Equal operator! This may

# show to you as an equals sign with a

# slash through it, but it's typed as

# '!' + '=' (!=)

print(british_capital != french_capital)TrueTry it yourself:

OK, so now we’ve seen comparisons and booleans, but why? Where are we going with this? Think back to the first lesson and the example of what is happening inside a computer: if the user has clicked on the mouse then we need to do something (e.g. change the colour of the button, open the web link, etc.). Everything that we’ve done up until now basically happened on a single line: set this variable, set that variable, print out the result of the comparison.

Now we’re going to step it up a level.

To check a condition you will need to use a statement (i.e. everything that makes up one or more lines of code line ) to see if that condition is True/False, in which case do one thing, or else do something else…

Let’s see that in action!

Let’s start with a basic if statement. In Python you write it:

So an if condition starts with the word if and ends with a colon (:).

The statement is the code that we want the computer to run if the condition-to-check comes out True. However, notice that the next line – the statement line – is indendented. This is Python’s way to define a block of code.

A block of code means that we can run several lines of code if the condition is True. As long as the code is indented then Python will treat it as code to run only if the condition is True.

Let’s see a few examples. Run the following code cell and see if you can understand the output produced (given the code in the cell).

# Condition 1

if 2 > 1:

print("> Condition #1")

# Condition 2

if 1 > 2:

print("> Condition #2")

# Condition 3

if "Foo" == "Foo":

print("> Condition #3")

myVar = 1 + 5

print(" My var: " + str(myVar))

# Condition 4

if "Foo" != "Foo":

print("> Condition #4")

myVar = 1 + 5

print(" My var: " + str(myVar))

print("Done.")> Condition #1

> Condition #3

My var: 6

Done.See how that works? Only conditions #1 and #3 were printed out, #2 and #4 were skipped over entirely!

Let’s take these in order:

condition-to-check returns True and Python then looks at the next line to see what it should do next.condition-to-check returns False. Python then skips the next two indented lines which form part of the code block. It’s the indentation that tells Python they’re still part of the same code block. That entire code block would only be executed if the condition-to-check had been True.!=) and so this condition is False. This time Python skips over the three lines and moves straight to the last print statement."Done.") always runs, no matter what the previous conditions were, because it is not indented and so is not part of a code block.Let’s see another example (run the code and check you understand the result)

Note: Other languages such as C/C++ use curly braces {...} around a block, just in case you find other languages in examples when Googling for help.

How much should you indent? Although the official specification specifies 4 spaces, quite a few people indent using one tab instead. Technically, there is no difference as long as you are consistent (See this discussion). This apparently trivial issue is the sort of thing that leads to all kinds of heated argument (like whether you prefer Mac OSX or Windows; OSX is better, obviously). It’s such a famous aspect of the programming world that it even featured in an episode of the sit-com Silicon Valley:

You can, of course, do multiple comparisons one after another:

london_population = 8600000

if london_population > 2000000:

print(str(london_population) + " is more than 2 million people")

if london_population < 10000000:

print(str(london_population) + " is less than 10 million people")8600000 is more than 2 million people

8600000 is less than 10 million peopleComplete the missing code, while also fixing the broken bits (HINT: Remember the position of colons and indentation is important in Python!):

Of course, only being able to use if would be pretty limiting. Wouldn’t it be handy to be able to say “if x is True: do one thing; otherwise do something else”. Well you can! When you want to run a different block of code depending on whether something is True or not, then you can use the else statement (only following a first if).

Here’s an example:

As you can see from the example above, the if: else: statement allows us to account for multiple outcomes when checking the logic of a condition. Notice how the else syntax is similar to the if statement: use the colon, and indent.

Also pay attention to the fact that not all of our code has run. Only the block after the else was run. So:

This is why the largestCity variable was set to “London” and not “New York”. After the if: else: sequence the code goes back to its normal flow, and all the remaining lines will be executed.

The if: else: statement is like a fork in the road: you can take one road, or the other, but not both at the same time.

Fix the code below so that it prints out London's population is above my threshold.

Once again: so far, so good. But what if you need to have multiple forks? Well, then you can use a sequence of statements that sounds like “IF this happens do this, ELSE IF this second condition holds do that, ELSE IF a third condition is true perform this other ELSE do finally this…”

The operator we are going to use is elif, the lazy version of ELSE IF.

# Like so:

myUpperBoundary = 12000000

myLowerBoundary = 2000000

if london_population < myUpperBoundary:

print("London is below my upper threshold.")

elif london_population > myLowerBoundary:

print("London is above my lower threshold.")

elif london_population != 340000:

print("London population is not equal to 340,000.")

else:

print("How did I get here?")

print("And now back to normal code execution.")London is below my upper threshold.

And now back to normal code execution.Why didn’t the output look like this:

London is below my upper threshold.

London population is not equal to 340,000.

How did I get here?

And now back to normal code execution.This a tricky one: the first thing that evaluates to True (that London is below the upper threshold) is the one that ‘wins’. Computers are also lazy in their own way: since it found that the answer to the first elif was True it didn’t bother to look at the second elif and the else, it only ran the one code block.

Complete the missing bits so that the logically correct print statement is output:

london_population = 10

if london_population <= 9:

print("First case is true")

elif london_population > 99:

print("Second case is true")

elif london_population == 4:

print("Third case is true")

else: print("Well, looks like none of the above statements were true!")

print("And now back to normal code execution.")Well, looks like none of the above statements were true!

And now back to normal code execution.Boolean logic and Boolean algebra have to do with set theory but also lie at the heart of the modern computer! A computer works by combining AND, OR, XOR and NAND circuits to produce ever more complex calculations (see this video and this one if you’d appreciate an introduction to/refresher on computer hardware). Naturally, we also use this same concept a lot in programming computers!

In Python there are three boolean logic opertors, these are (in ascending order of priority): or, and, and not.

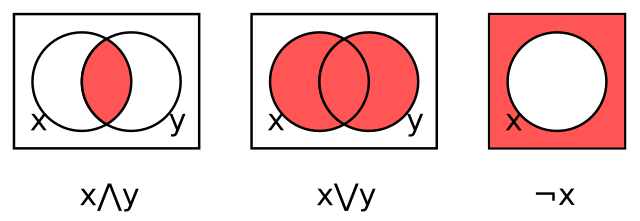

We’ll look at these in more detail in a second, but here’s the ‘cheat sheet’:

It might help you to take a look at these Venn diagrams (source: Wikimedia Commons) that express the same three operations in graphical form. Imagine that x and y are both conditions-to-test… The left one is AND because it is only the combination of x AND y that is red; the centre one is OR because it represents any combination of x OR y being red; the rightmost is NOT because it is the opposite of x that is red.

OK, let’s look at it in Python.

The and operator (just like in plain English!) is used when two conditions must both be True at the same time. So it has two arguments and returns True if, and only if, both of them are True. Otherwise it returns False.

condition1 = 2 < 4 # True

condition2 = (6/3) == 2 # Also True

if (condition1) and (condition2): # Both are true

print("1. Both conditions are true!")

else:

print("1. Mmm... something's wrong!")

if condition1 and 6.0/5 == 1:

print("2. Both conditions are true!")

else:

print("2. Mmm... something's wrong!")1. Both conditions are true!

2. Mmm... something's wrong!The or operator is used when we don’t care which condition is True, as long as one of them is! So if either (or both!) conditions are True, then the operator returns True. Only if both are False does it evalute to False.

condition1 = 2 < 4 # True

condition2 = (6/3) != 2 # False

if (condition1) or (condition2):

print("1. Both conditions are true!")

else:

print("1. Mmm... something's wrong!")

if 2 > 4 and 6.0/5 == 1:

print("2. Both conditions are true!")

else:

print("2. Mmm... something's wrong!")1. Both conditions are true!

2. Mmm... something's wrong!Try to change the values of conditions and see the different outcomes, but first you’ll need to fix the Syntax Errors and the Exceptions!

Lastly, the not operator allows you to reverse (or invert, if you prefer) the value of a Boolean. So it turns a True into a False and vice-versa.

Can you guess the result of this code before you run it?

The aim of the excercise is to build a program that allows a user to choose a given London borough from a list, and get in return both its total population and a link to a OpenStreetMap that pin points its location.

We are going to introduce a function called input that, as the name implies, takes an input from the user (interactively, that is!). We’ll use it to interact with the user of our program. The input is going to be saved in a variable called user_input.

I’ve provided a basic scaffolding of the code. It covers the case where the user choses the City borough, or provides an invalid input. Complete the script so that the three other boroughs can be found by the user.

HINT: You will need to use elif statements to check for the various cases that use user might input.

# variable with the City borough's total population (in thousands)

city_of_London = 7.375

# City borough's map marker

city_coords = "http://www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=51.5151&mlon=-0.0933#map=14/51.5151/-0.0933"

# Other boroughs

camden = 220.338

camden_coords = "http://www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=51.5424&mlon=-0.2252#map=12/51.5424/-0.2252"

hackney = 246.270

hackney_coords = "http://www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=51.5432&mlon=-0.0709#map=13/51.5432/-0.0709"

lambeth = 303.086

lambeth_coords = "http://www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=51.5013&mlon=-0.1172#map=13/51.5013/-0.1172"

# Let's ask the user for some input

# and store his answer -- this doesn't

# work in a non-interactive shell

try:

# Let's ask the user for some input

# and store his answer

user_input = input("""

Choose a neighbourhood by type the corresponding number:

1- City of London

2- Lambeth

3- Camden

4- Hackney

""")

except:

# We're running the browser most likely

user_input = '1'

# Arbitrarily assign case 1 to City of London borough

if (user_input == '1'):

choosen_borough = city_of_London

borough_coordinates = city_coords

# print the output

# notice we are casting the user answer to string

print("You have choosen number : "+ str(user_input))

print("The corresponding borough has a population of "+ str(choosen_borough) +" thousand people")

print("Visit the borough by clicking here: " + borough_coordinates)

elif(user_input == '2'):

choosen_borough = lambeth

borough_coordinates = lambeth_coords

# print the output

# notice we are casting the user answer to string

print("You have choosen number : "+ str(user_input))

print("The corresponding borough has a population of "+ str(choosen_borough) +" thousand people")

print("Visit the borough clicking here: " + borough_coordinates)

elif(user_input == '3'):

choosen_borough = camden

borough_coordinates = camden_coords

# print the output

# notice we are casting the user answer to string

print("You have choosen number : "+ str(user_input))

print("The corresponding borough has a population of "+ str(choosen_borough) +" thousand people")

print("Visit the borough clicking here: " + borough_coordinates)

elif(user_input == '4'):

choosen_borough = hackney

borough_coordinates = hackney_coords

# print the output

# notice we are casting the user answer to string

print("You have choosen number : "+ str(user_input))

print("The corresponding borough has a population of "+ str(choosen_borough) +" thousand people")

print("Visit the borough clicking here: " + borough_coordinates)

else:

print("That's not in my system. Please try again!")You have choosen number : 1

The corresponding borough has a population of 7.375 thousand people

Visit the borough by clicking here: http://www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=51.5151&mlon=-0.0933#map=14/51.5151/-0.0933The following individuals have contributed to these teaching materials: - James Millington - Jon Reades - Michele Ferretti

The content and structure of this teaching project itself is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 license , and the contributing source code is licensed under The MIT License.

Supported by the Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) with a Ray Y Gildea Jr Award.

This lesson may depend on the following libraries: None